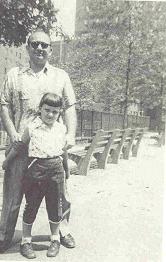

Playground 5; The author with her father

Black and White

His Graflex, Rollei, Canon, Leica

were his voice; he didn't speak,

but he recorded his poetry

on film, writing with light,

on endless rolls

of silver-coated, sprocketed curls

that he would load into his cameras

and shoot.

When the number in the little window, or on

the turning metal indicator reached twenty-four

or sometimes thirty-six,

he would rewind the film and remove it

from a trap door.

Then we would go into the closet

where it was black, and silent,

between the coats,

so quiet you could hear

the blood rushing through your ears,

except when he was loading the film

into the developing canister;

swoosh, swoosh, swoosh.

The Kodak man stayed securely

in my hand, glowing in the dark, greenish,

a plastic profile of a cartoonish man

in a 1950s hat, like a news reporter,

holding a camera, like my father's.

Maybe the Kodak man was meant to swing on a

chain to turn a red safety light on and off,

but he was mine.

In the kitchen the film was loaded, developed,

bathed and unwound.

He put the strips into the enlarger

that sat next to the broiler

and cooked up images of

the Lower East Side;

buildings, people, interaction,

then burned them with light

onto the paper,

and bathed them in a vinegary pond

in a pan in

the kitchen sink.

Up came the images, darker and clearer;

the faces, the streets, the tenements,

the sky, the people sitting near the

East River.

The family. Me.

Perserved happy moments

of light-jelly in paper jars.

The poetry of his Graflex,

calling for future stanzas to be written

by a then

Kodak Brownie.